It is acknowledged that pain is a difficult thing to describe with any accuracy, but as a physical sensation, it is the one that weighs most heavily on our lives. Sinead Gleeson takes on this challenge in her book of essays Constellations, a collection of prose and poetry which maps physical pain as well as emotion onto the body, onto her body, onto the body of women and, specifically, onto the body of Irish women.

“Illness is an outpost: lunar, Arctic, difficult to reach. The location of an unrelatable experience never fully understood by those lucky enough to avoid it.” This comes at the beginning of an essay about how women have expressed their own pain in their art, from Frida Kahlo to photographer Jo Spence and the writer Lucy Grealy, artists who Gleeson has found solace in over the years.

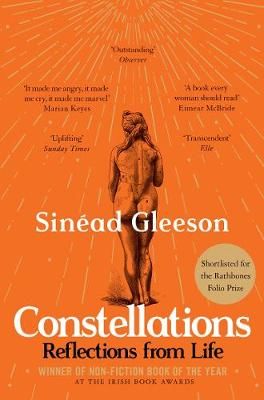

This book is sublime. Every phrase presents itself to be devoured and then lingered over, returned to and clung on to. Gleeson writes about the every day, though her every day has been tougher than most. She has experienced a lot of physical pain, from early on in life, from multiple stays in hospitals and orthopaedic interventions to a lung clot, leukaemia, breast cysts, pregnancy, nerve damage…

To try and name her pain, she uses the 77 words given to describe pain on the McGill Pain Index. Pricking, boring, drilling, stabbing she gives to her lumbar puncture. Punishing, gruelling, cruel, vicious, killing are attributed to unlistened to pain, a type of pain which features throughout the book, thanks to the many doctors and medical professionals who have ignored or not listened to Gleeson, made poor decisions for her pain and impacted her suffering. I have direct experience of this. I expect most women who’ve ever consulted a doctor have. Often this leads them to give up, to put up with their pain, to prevent them from seeking further help, to believe that they can, or they should.

“Rendered public, making the experience of pain political - to borrow Hannah Arendt’s assertion that any act undertaken in public is a political one. Women learn early that absorbing pain is a means of martyrdom inching us closer to the bodies of saints as if discomfort equates to religious ecstasy. That there is meaning in suffering, except that there is not.”

Gleeson is Irish. Constellations won the Irish Book Awards nonfiction book of the year in 2019. Writing about the body has a specific meaning in the context of Ireland, of its history of Catholicism, of stealing babies, of forcing unmarried mothers to work in the Magdalene laundries like slaves. Of denying contraception, healthcare, abortion to women regardless of the danger they were in. Of allowing women to die rather than risk the life of an unborn baby.

But this isn’t a miserable book, far from it. It finds beauty in the excruciating and humour in the oppressive. It reveals the glory of the lives of the older women in Gleeson’s family, despite the pain and privation they lived their whole lives with. She writes “the physical experience resists words, refuses to reside in letters” and quotes Virginia Woolf’s assertion there is a “poverty of language” to describe pain. And yet Gleeson has pulled this off. We cannot feel her pain physically, of course, but we can approximate the damage it has inked her with. We cannot live the lives of the Irish women deprived basic human rights, but we can hear about them and empathise and offer some solidarity in our own pain. We can hope to live with far less pain than Gleeson has endured, but we know when it comes we will feel it, we will struggle to name it, we will have to fight for others to accept it is there.