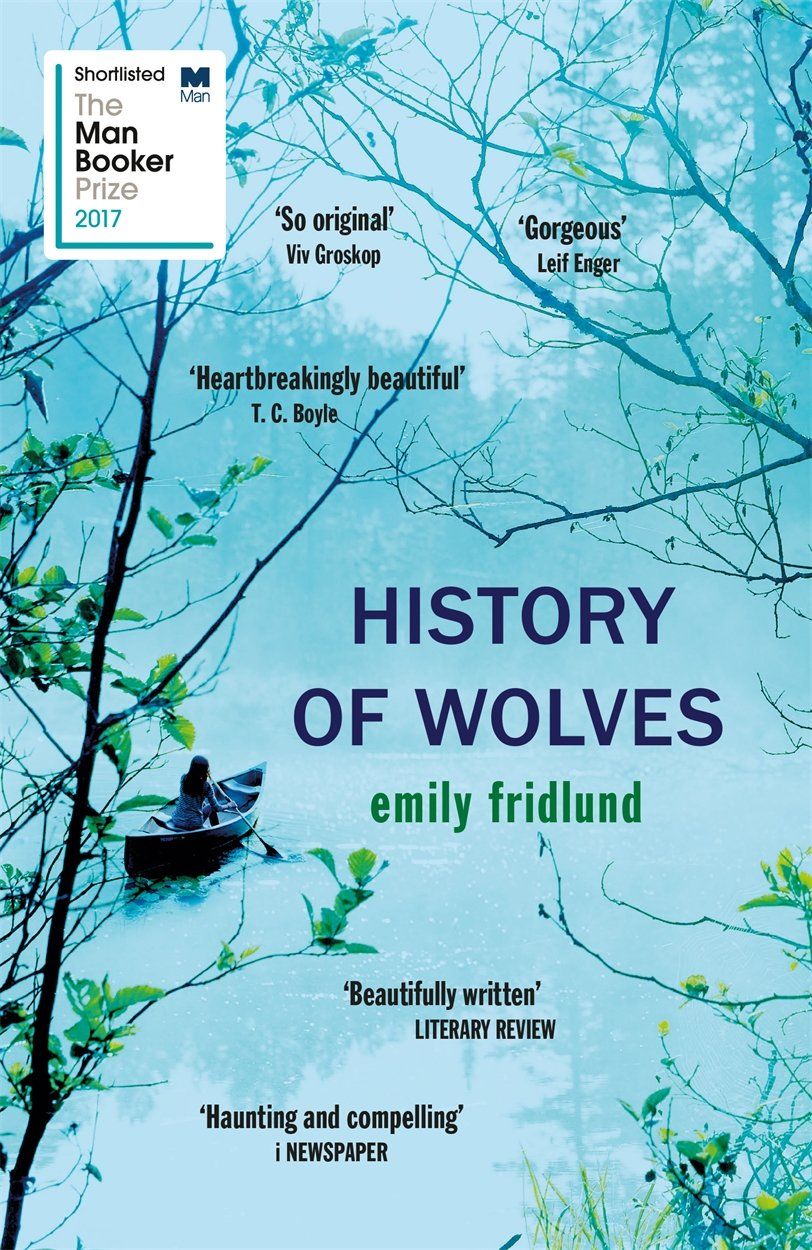

History of Wolves, Emily Fridlund

The backwoods setting of this miserable, but intensely lyrical, debut aligns itself with an image we know and have come to accept about contemporary America. The characters live in a rural area, the distances travelled daily as hard to overcome as the gulf of opportunity. Their lives are dressed in danger upon danger: parents are neglectful, predators lurk, the natural world is all powerful. Around this spins a web of many strange beliefs and judgments, the individuals in thrall to some greater mystic power – religion – like the country as a whole.

Linda, Fridlund’s protagonist, is a 14-year-old misfit living in poverty by a lake in Minnesota. Her parents, the only couple left from a cult they helped to found there, are shadowy influences: not malign, but nowhere near involved enough in Linda’s life. They offer no protection. She is gawky and friendless, and does odd things she knows are odd, such as egging on the interest of a creepy teacher. But her interest in the woods she lives in, the foundation of a talk she gives on the titular history of wolves, is enchantingly rendered and reminds us of the beauty of these areas, and why so many different groups of people sought (and still seek) solace and freedom in such places.

Linda decides to seek her solace on the other side of the lake, when a couple from the city move in with their young son Paul, who she babysits for the mother, Patra, while the father is away working. This family, apparently educated, middle class, interesting, and interested in Linda, are as strange and untrustworthy as her own family. After all, we know from the start of the book that Paul has died, and we know his death can only be connected to the lake and those living there.

Patra and Leo turn out to be Christian Scientists, who refuse to seek treatment for their sick son. Linda is implicated insofar as she is too naive to fully understand what’s happening, and to seek help, before it is too late, but she is intoxicated by the idea of parents who might care for her as kids are supposed to be by their parents – which she wrongly recognises in Patra initially.

I read a Guardian review that said this novel is a coming-of-age story which falters because it lacks the joy of that genre. I don’t agree that a novel with a teenage protagonist has to be a coming-of-age story, even when they’re looking back at events that shaped them. Linda is so unusual for a teenager she makes a compelling character. You want her to succeed while wondering at her motives. The book reveals so many adults who act as children, wilfully following the diktat of someone else, because it’s the easiest way to go, that it is unclear who are the children and who the adults, who might be coming of age, and who is culpable, alongside religion and blind belief.