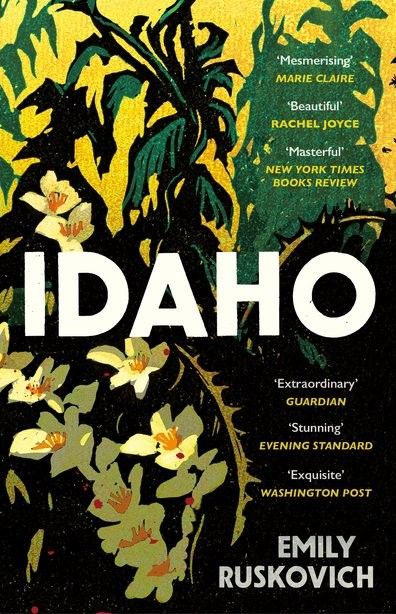

Idaho, Emily Ruskovich

They say women and their hormones can’t cope with sad stories during or soon after pregnancy, but my book choices this year have been uncommonly skewed towards stories of dead children, and parental infanticide. Maybe it’s a sign of the inevitable break between baby and breast which has partially freed me to be a human being in the world again.

The first of these was chosen by Erin for the inaugural instalment of the Isle of Death bookclub, and I found Idaho one of the most astonishing and terrifying pieces of writing I have ever read – in a good way. I had borrowed the paperback from my library and kept renewing the loan; even though I didn’t get round to re-reading I had many a mini browse.

The book opens with ‘the terrible event’, and is seen from the perspective of Ann, the second wife of the bereaved father. The mother is in prison. Life on a hill in Idaho is hard, really hard, but this is no exposé of fucked up hillbilly farm life. Ann grasps throughout for the key to the tragedy, trying to match hints to clues then verify these, while her husband Wade’s memory drifts into dementia. There’s a light-as-air quality to the writing, which slips away through the dense and treacherous landscape like wind whistles through grass.

I can’t believe this is a debut. Ruskovich must have twenty other novels under her bed. The ease with which she dances between the present time and that of the tragedy, in the mid-90s, is deft, and then she shows us she can push further, and brings us to the mother, Jenny, at the time she was building her hilltop home with Wade, spending a pregnant winter there snowed in, and then on to her prison existence. The shifts in viewpoints are equally frequent and fluid.

Ruskovich scratches at the door of human possibility here. What can we do? What might we do? How can such things ever be explained? Some members of the book group agreed that despite the horror of the story, they’d felt reassured knowing they’d never find themselves in that situation. I felt chilled: for me it was a warning that one split-second event can colour the rest of your life, whether that’s not looking before crossing the road, letting your child climb too high on those rocks, or losing your temper at the wrong moment.

£12.78, Random House, Feb 2017