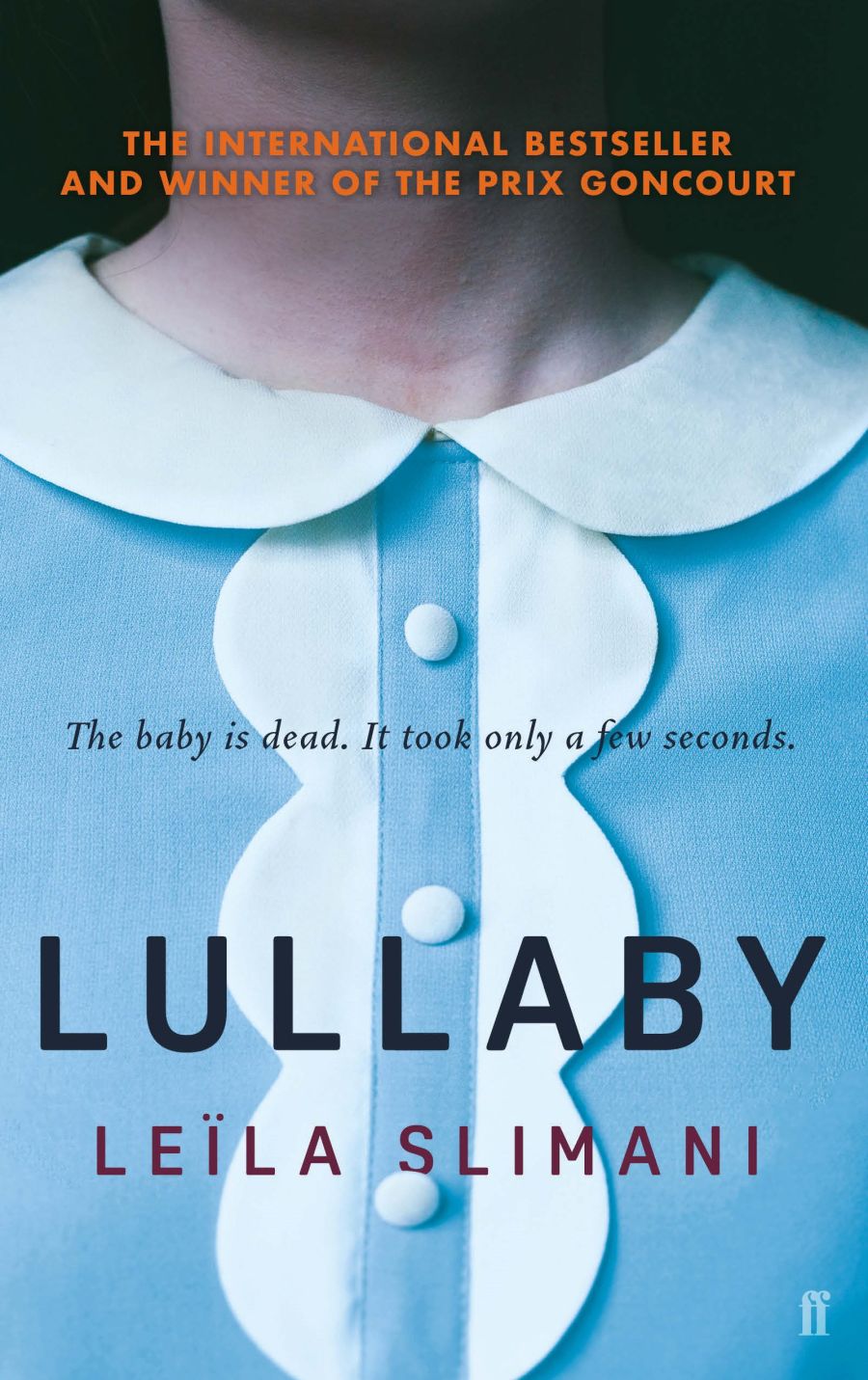

Lullaby, Leila Slimani

Lullaby was a mega hit when first published in France. Its author, Leila Slimani, is a French-Moroccan journalist and now one of Macron’s darlings, and this book won her the prestigious Prix Goncourt. I’m not alone in being wary of anticipation. With books and with films, the more hype I read, the more I fear I’ll find my experience wanting. And so it was with Lullaby, a book I found intriguing, and clever, and desperate, and also a book which asks so many questions to which Slimani well knows have no answers – this is how it should be, but sometimes I want a book to complete me, and Lullaby is fantastic but feels like a single note when I’m after the full rave.

It is a book, oddly like many I have been drawn to this year, about a dead child: two children, murdered in this case by their nanny, their perfect nanny, Louise. This isn’t because I am drawn to dead children, but to the close investigation of how children, and lack of them, can affect women, people and families.

Opening at the terrible scene of the crime, Slimani then traces the story backwards. How could a woman this devilish be in charge of children? How could she succeed in so misrepresenting herself to her employers, now grieving parents? How could the parents, so preoccupied with work and living, allow this woman into such proximity with their family, but fail to do due diligence on her background? Why do they overlook her needs – an arrogance, Louise appears to feel, which pushes her to the final act?

The way Slimani writes of the family’s small, daily routines, and how they interact with this stranger in their house, is carefully observed, bum-clenchingly honest, and chilling. There are power struggles on many levels. Louise is Myriam and Paul’s employee, yet she has access to much of their private lives. She spends more time with their children, who behave better for her, but she can be sent away from them at any moment, such as when they holiday. Myriam and Paul both work, but it is Myriam who carries the burden of leaving the children when she returns to work, and has to question her choices. Louise attends to their every whim, but sometimes her employers behave like she doesn’t exist. They offer her, it is intimated, the sort of family life she never enjoyed herself, then cruelly pull back. They don’t appreciate at all that she does have a past and an outside life, the pressures of which will bring to bear on her sanity and her actions.

Like most of the other nannies in the park, Louise is North African. She is an outsider. The battle in Lullaby’s pages is a universal one: Louise feels excluded, and she wants to be included. She feels that she works very hard, harder than anyone else, to achieve this, but it’s ultimately denied to her. She cannot cope with this. She enters a psychosis. The result is unspeakable violence, which benefits nobody and ruins many. This blueprint, applied to the wider power and political dynamics in France and elsewhere, is terrifyingly bleak.