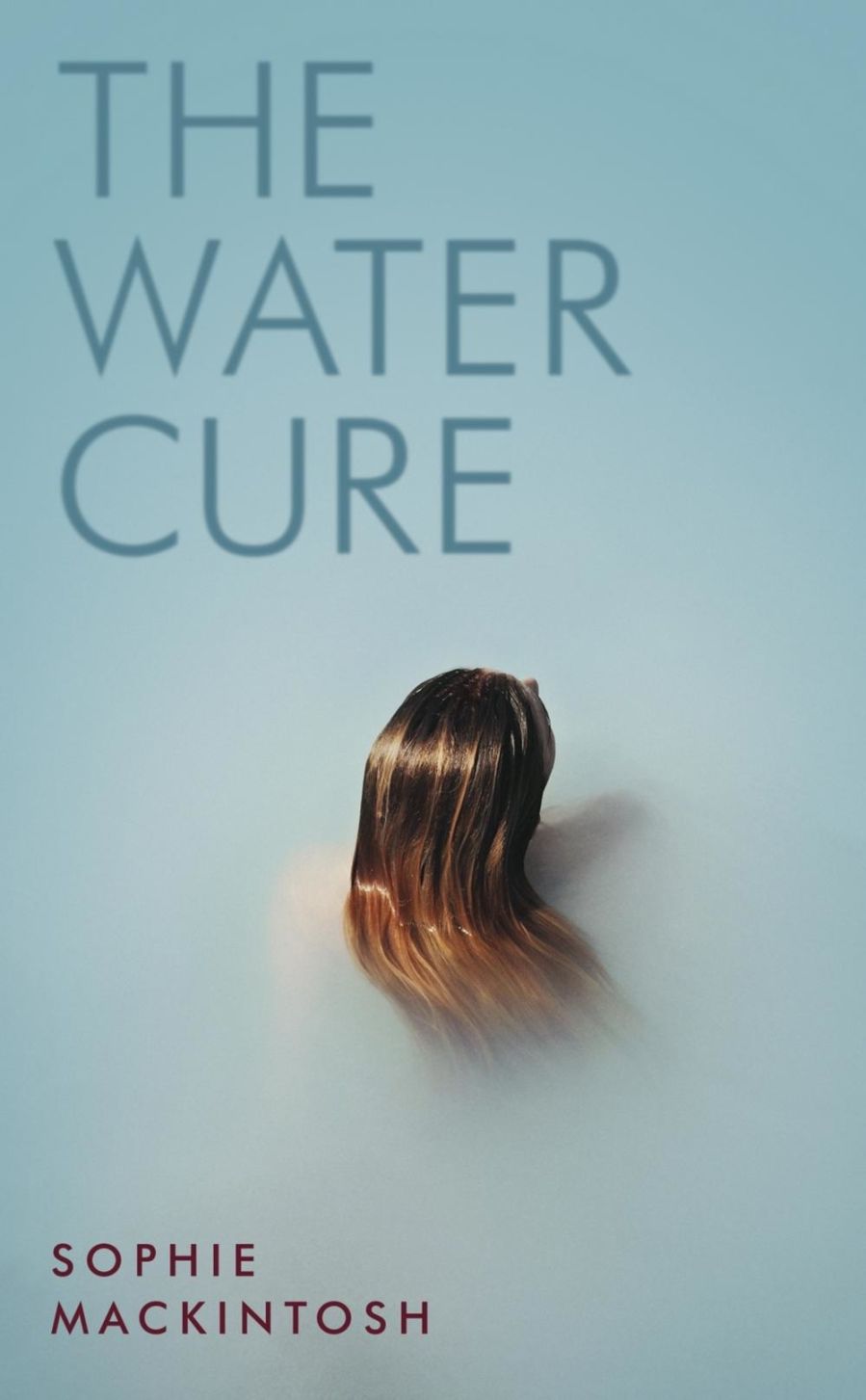

The Water Cure, Sophie Mackintosh

I bought this in a rush of excitement at all the female authors on the Booker Prize longlist, but The Water Cure is a very painful book to read if you’re a woman, are related to any women, or know any women. Even more painful if those women are still girls. Its protagonists are three sisters, Grace, Lia and Sky, who live with their parents Mother and King within the safe confines of an island, far from the toxic world beyond, where men cannot help but harm women, with their breath and their bodies, as well as their thoughts and intentions. They seem to live in a secure and pure land, while the outside world is a post-apocalyptic over-polluted hell.

It is also a strange and confusing novel. I found it beautiful, but Mackintosh has created such an unsettling and otherworldly world, it took me a while to get on with it, and longer to read than I’d hoped. Part of this is down to the richness of her language; it’s so intense I found myself stopping and thinking after almost every phrase, which took me out of the story.

The sisters have been brought up practising all sorts of physically painful and emotionally traumatic tricks, tests and games in order, it seems, to save them from the reality of the outside world, where love means pain and women are always in danger. They choose ‘favourites’ from amongst the family members for each year, though someone is always left without, to discover what it feels like to be alone. They are punished for certain actions with rites of physical torture, such as rubbing away at their skin with sandpaper, until many layers have been pulled off and a bloody wound left behind.

Women used to visit their island to seek healing from Mother and King, but they stopped coming some years before the novel begins. We learn that the water cure is a dangerous ritual their parents have developed where they and the visiting women are held under water, holding their breath, until the last moment. The girls regularly practise for this, sometimes wearing ‘drowning sacks’.

King goes for provisions from the mainland and never returns. Then three men wash up on the shore, and the girls have to work out if and how they can trust them. Mother is angry if they communicate with them. Grace is wary. Lia cannot resist their charms. Finally they all have to work out how to survive as the danger mounts.

When the fullness of the failed idyll King and Mother forced upon their daughters is revealed, the effect is crushing. For all we know, we realise, the outside world could be much safer than the ‘island’ they have been brought to. It could be as safe as Gilead was before it became Gilead – imperfect in so many ways, but not a totalitarian environment built on control and fear, as King creates. The physical and mental torture he wreaks on his daughter’s and his idiot enabler Mother, is terrible to think about, as is the way that Mackintosh has managed to use such beautiful and lyrical language to show us such an awful place.