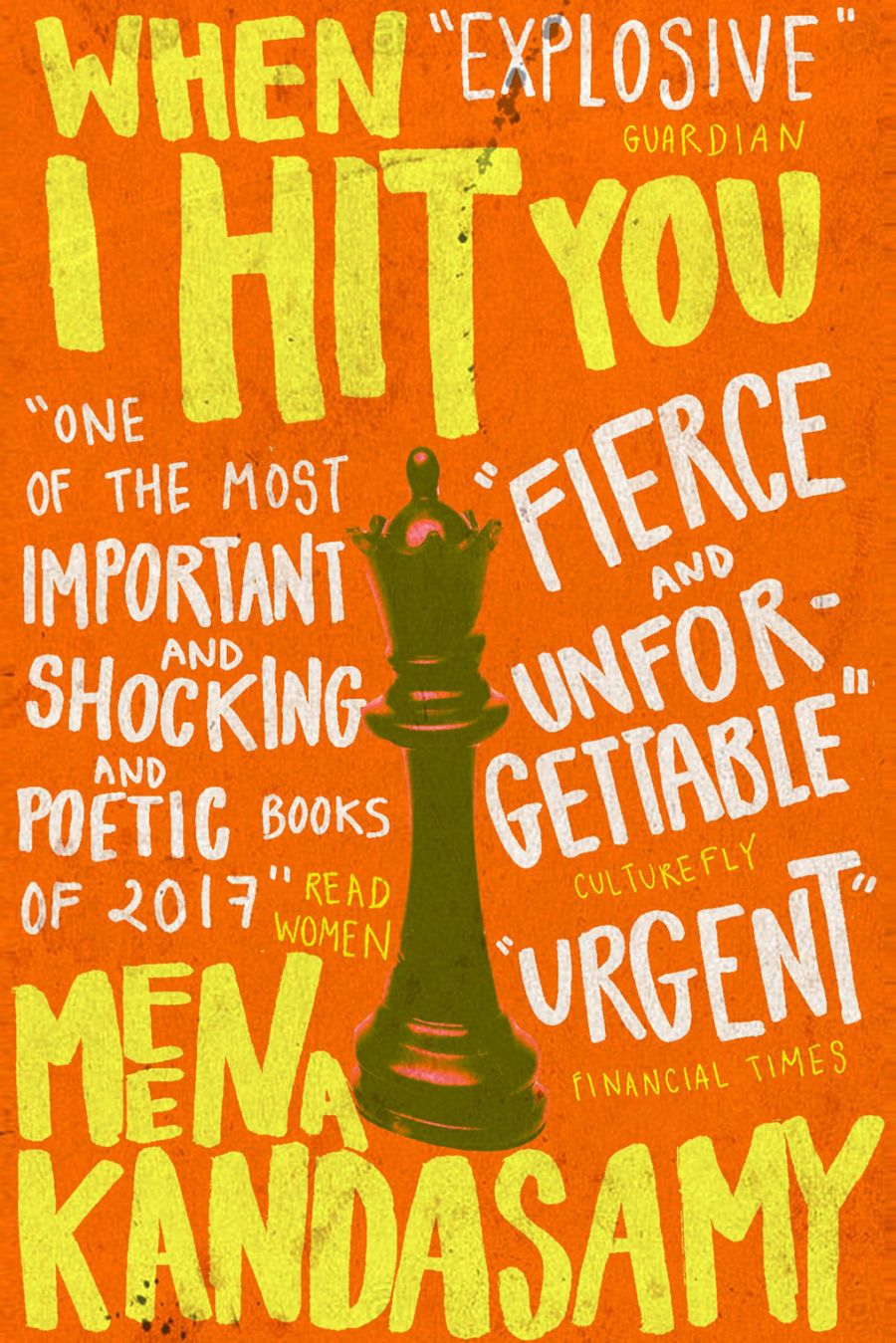

When I Hit You, Meena Kandasamy

When I Hit You sounds like just the barrel of laughs we’re told there’s no market for: yes, heinous violence is acted out on innocent women, but unusually the victim lives to tell the tale. The narrator, a young Indian woman, barely out of university and already married to a violent, oppressive man, a university professor she married in haste and on the rebound, reveals at the beginning of the book that she escaped her tormentor five years earlier but that her mother has still not got over it. Of course, you think: how could a mother get over the fact her daughter had endured such terrible beatings and mental torture? But really it’s the shame her mother hasn’t got over, and to reduce the shame she’s taken ownership of her daughter’s ignominious return to the family home, and turned the story into one of the health and hygiene consequences of the domestic torture, instead of the real story power and violence.

The narrator decides she must wrest the story back into her own hands, her own head, her own words, and returns to the beginning to explain how it was so very easy to fall into a desperately abusive relationship, and so very complex to finally extract herself.

This meta conversation continues throughout the short novel, which was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2018. Our narrator, a writer, is isolated socially from her friends and family, before her husband begins to be violent, carrying out acts which Kandasamy describes unflinchingly. The writing is very often painful to read; we’re trapped in the tiny home of this terrible marriage, rooting for the wife to escape, putting all our eggs, like her, in her weak escape plans.

It’s too easy to categorise this story as one only about Indian women, set in a world which white westerners are insulated from. Although the level of shame and the unwillingness to intervene from her family is shocking, the story is still universal: a highly-educated and politicised middle class girl hooks up with an older man and is mesmerised by his wit and intellect, before finding she’s trapped too, by his brutality and bigotry, insecurity, small-mindedness and hatred. These are things suffered by women of all races and classes and means and levels of independence. Everyone should read this book, but short of that it could be on a compulsory reading list for domestic abusers.