What came first - the rise in new varieties going on sale, the fetishisation of brunch, or the fact that eggs are the most versatile ingredient around? Sophie Morris dips in

You might have snacked on a quail’s egg, or fried porcelain-white duck eggs for a special weekend brunch, or simply wondered at some of Waitrose’s more outré ovum offerings (it’s had pheasant and ostrich eggs on its shelves, and is now selling an emu egg for £23.99).

None of these, even the emu, has anything on the regal tinamou egg, a gleaming specimen that naturally comes in colours ranging from green to gold to purple, glossy as an oil slick and farmed only in one spot - towards the southern tip of Chile. Move over Fabergé, this egg comes ready gilded.

Educating food lovers about this rare South American egg is what happens when the world’s hippest food publisher decided to “do” eggs. Lucky Peach, the cultish quarterly food magazine from New York chef David Chang, has just published its second book, All About EGGS (£19.99, Penguin Random House). It will be a swan song for the publication, which recently announced it was closing.

To say that eggs are having a moment would misrepresent our enduring taste for dipping buttered soldiers into melting orange yolks, gently scrambling buttery golden pillows, and whisking whites to form meringues. Still, a growing appreciation for meat-free meals, a revival of breakfast and brunch as proper, not-to-be-skipped occasions, plus an appetite for trying out more Middle Eastern and Asian recipes at home, means we’re looking at eggs with fresh admiration.

Health fears about eggs have also been overcome. The misconception that yolks were a contributing factor to heart disease has been widely discredited.

The British Heart Foundation ended its advice to limit eggs to three a week in 2007. In 2015, the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee in the US finally admitted that it was unlikely for foods containing cholesterol to affect cholesterol levels in the blood, a myth propagated by the American Heart Foundation at the behest of the then First Lady Mamie Eisenhower,after her husband Dwight D Eisenhower’s heart attack in 1955.

Last year, a government food safety committee announced that even pregnant women, who have been advised to avoid raw eggs since they were linked to salmonella in 1989, can eat raw or lightly cooked eggs, as long as the eggs carry the red British Lion stamp.

“In the West, when we hear raw eggs we think of Sylvester Stallone in Rocky,” says All About EGGS author Rachel Khong, who lives in San Francisco. “But that’s not necessarily the case in other countries. In Japan, tamago kake gohan (TKG) is a raw egg cracked over rice. In Vietnam, you can get an egg soda, which is a raw egg mixed with condensed milk and soda water.

“Raw eggs are also great for emulsifying sauces or salad dressings or on top of steak tartare. If you buy your eggs from a trusted source, I don’t personally believe there is any reason to fear. That said, you should follow your heart. Don’t take my word for it, and please don’t sue me!” According to another egg bible, Posh Eggs (Quadrille, £12.99), we eat 32 million eggs every day in the UK, so it’s time we found some new ways to cook them. How about foo yung, a lacy golden omelette served with crunchy veg, roast pork and a sweetand-salty gravy? The recent publication 100 Ways with Eggs (Ryland Peters & Small, £14.99) includes recipes for boozy treats such as a whiskey sour and a gin fizz.

Even the Hairy Bikers have turned their attention to eggs with The Hairy Bikers’ Chicken & Egg, a practical paean to these two crowd-pleasing ingredients.

All About EGGS explores the science behind eggs, and shares basic knowhow such as how to make perfect boiled, fried or poached eggs, and how to tell if your egg is fresh.

It also has recipes from cultures as diverse as Korea (Korean steamed eggs), Turkey (menemen, or eggs with tomatoes and peppers), Japan (tamagoyaki), Spain (tortilla) and, of course, our very own Scotch eggs.

There are “chipsi mayai”, chips and eggs from Tanzania, Pisco sour cocktail, the Peruvian national treasure, stinky Chinese century eggs, and American diner staples such as the Denver omelette (pepper, ham, cheese and tabasco) and the hang-town fry, a Gold Rush-era bacon and oyster omelette.

Khong also shares fascinating tales of ovoid love and lore out of great food writers, such as Harold McGee, who investigates how best to peel hard-boiled eggs, while an essay on egg tarts travels from Hong Kong to Macau to Portugal, giving eggs the full Lucky Peach treatment. Other stories tackle pressing questions: “Why do we eat eggs for breakfast?” and “How to understand an egg”. Nothing but the best for an ingredient Khong calls “the world’s most important food” and “a cornerstone of being human”.

Eggs of the I learned and learning master “I am mostly joking when I make the myriad grandiose claims about eggs that I do,” she explains. “But I do in fact believe that eggs are amazing, miraculous things, and I think it’s good to be in touch with one’s sense of wonder.

“I have always loved eggs. They were one of the first foods I learned how to cook, yet I’m still learning to master them. And humans have been eating eggs since before recorded time. Cooks and chefs are often en-amoured with eggs, for a million reasons. A book about eggs seemed like a no-brainer.”

Love her or hate her, Elizabeth David’s immortal omelette-and-aglass-of-wine is echoed in what many chefs eat on their day off, as well as something they prepare to show off.

All About EGGS stretches from highbrow cheffy eggs down to the everyday.

were one first foods to cook I’m still to them There’s the Arzak egg (from three Michelinstarred Juan Mari Arzak), another three-star egg in Alain Passard’s Arpège egg, and Daniel Boulud (three stars until 2015) offers a down duvet of a dish, his omelette farcie (stuffed omelette).

But there’s also the egg banjo, a “troop treat food” of a fried egg held between two thick slices of often stale white bread, brushed with butter and wrapped in greaseproof paper. You can’t add anything to make this more fancy: if you did, your banjo would graduate to sandwich territory.

Eggs have too many laudable qualities to list. They have roles in fields as diverse as medicine - eggs are used to extend the life of semen used in artificial insemination, and producing the flu vaccine claims over a billion eggs every year - and art, as vivid egg tempera paint was routinely used by artists including Botticelli before it was superseded by oil paints in the 1500s.

And for those fed up with finding broken eggs in the carton, Khong reports that eggs are surprisingly strong, and can even survive the weight of a person walking over them. “The tops and bottoms of the egg are the most strong, and the curve of their shell distributes pressure evenly. So that’s why hens can sit on eggs without breaking them.”

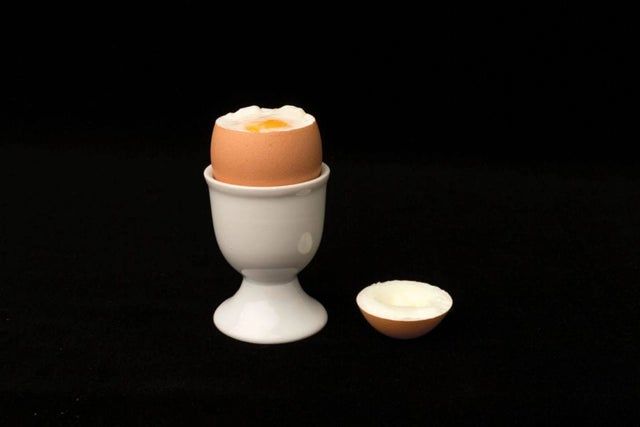

Boiled egg Ah, the boiled egg - easily adorned, yet impossible to improve upon. Whether softboiled or hard-boiled or somewhere in between, a boiled egg refers more to an outcome than a cooking method, as an egg cooked in its shell to a firm white with a runny or hard yolk is often not cooked in boiling water, rather boiled water that reaches some equilibrium with a cool egg.

SOFT-BOILED EGG(S) Makes 1 to 12 eggs 1. Bring a large saucepan of water to the boil and gently add the egg(s). Stir the water and egg around the pot for 60 seconds. This will center the yolk inside the egg white, yielding a more evenly cooked egg. Stop stirring and simmer the egg, reducing the heat as necessary to maintain a light bubble, for 3½ minutes longer.

2. Remove the egg and plunge into an ice bath. When the egg is cool enough to handle, peel it carefully. Alternatively, set the hot egg in an eggcup and use an egg topper to remove the pointed end of the egg. Serve with a small spoon and toast soldiers.

HARD-BOILED EGG(S) Makes 1 to 12 eggs 1. Put the egg(s) in a saucepan of cold water and bring to a full boil. Once you see big bubbles, remove the pan from the heat and let stand 8 minutes for a fudgy yolk, 10 minutes if you’d like the yolks firmer. Plunge the egg(s) into an ice bath and let cool.

2. Crack the egg(s) against a flat surface. Peel the egg(s) and rinse under running water to remove any bits of shell. Eat right away, or refrigerate until ready to serve.

Note: Cooking more than 12 eggs with these methods will require a larger pot, more water, and possibly an increased cooking time.

Taken from ‘All About EGGS’ Fried egg, I’m in love! There are probably thirteen ways of looking at a fried egg, but here are four ways to cook one. A sunny-side up egg has a purely white albumen that is fully set, including where it meets the yolk and the yolk is not opaque or coagulated but warm to the palate. An over-easy egg has a purely white albumen that is flipped and fully set. The yolk is warm and the outside of it is coagulated. When cut, the yolk will run past the edge of the white. An over-hard egg has a fully set, pure white albumen, flipped and cooked so the yolk will not run, though it retains a creamy and not chalky consistency. An overmedium egg lands in between.

Makes 1 egg + oil, butter, lard, or other edible fat 1 egg + salt 1. Warm a teaspoon of fat in a small nonstick skillet over medium-low heat. Crack the egg into the pan and run a heat-resistant spatula through the egg white where the cohesive albumen meets the runnier albumen. This will create a uniform white.

2. Cook the egg undisturbed until the white is set. Doneness can be tested by dragging a spoon across the white near where it meets the yolk; the white should collect in the spoon in a soft curd, like a scrambled egg. It should not be rubbery. Depending on the size of your pan and burner, it will take 60 to 90 seconds to reach this stage. This is a sunny-side up egg.

3. For an over-easy egg, flip the egg and cook for 15 seconds, sealing the yolk in coagulated protein.

For over-medium, cook another 15 to 30 seconds, until the yolk feels like a cheek when poked. The yolk will have thickened but not be firm throughout. For over-hard, continue cooking another 30 seconds, until the yolk feels just like where your thumb meets your palm. It should be firm but creamy. Slide on to a plate, season, and serve.

Taken from ‘All About EGGS’