I’m not sure which I acquired first, a husband who can’t cook or a husband who won’t cook. To be clear, he never misrepresented himself. From the soupy slurry of vegetable pasta that Ben made the first time he cooked dinner for me, in late October 2011, to ongoing escapades with carbonised garlic and avalanches of black pepper, he never claimed to be interested in the process of cooking or even, very often, the outcome.

For Ben, eating was a means to an end (survival). For me, every meal is an opportunity for pleasure, comfort, perhaps experimentation, but definitely not an occasion I’ll spoil with bad food or burnt food, under-seasoned or over-cooked food, poor ingredients or conflicting flavours…you get the picture.

It’s nothing to do with making expensive or impressive food; I’ll honour a cheese sandwich made with a sliced loaf and supermarket cheddar as much as a Saturday night dinner. But my obsessive attention to details that I consider simple, incontrovertible truths has turned me into a kitchen tyrant, my husband believes, and he is understandably wary about challenging me.

Our kitchen wars

As a couple, our kitchen antagonism has ebbed and flowed over the years. Ben successfully fed himself once or twice a day before we met, he often reminds me, before I swept in and decreed regular meals at typical times in which ingredients had been cooked together into a recognisable dish, probably following a recipe, not blasted with heat then brutally dumped beside each other to serve. But I always loved cooking and was happy to do it all. Besides, it’s an easy way to shirk most other household duties

I didn’t mind until five years on, when we had our daughter. The divisive cliché of domestic labour kicked in hard. It was the first time in my life that I hadn’t felt like cooking, nor could I carry shopping or stand and stir for the initial months. I was starving. Sure, I had a tiny infant cannibalising whatever energy I did ingest, but mostly what I remember of that time is how hungry I was. I adore peanut butter, but it won’t sustain me through a full day.

I could have used that experience to empathise with Ben’s absence of desire in the kitchen, but it made me want him to become a confident and capable cook even more. I wished he would lust after roast chicken as much as I did, and become equally turned on by salt on chocolate brownies or homemade pesto. Simple things, I thought, but things that mattered. What did he think about all day, if he wasn’t wondering what we’d eat that evening, or how to shop and cook for a houseful at the weekend? Surely someone could split the atom in the time I spent planning and preparing family meals?

This thinking time, which usually falls to women, can be referred to as “mental load”, “invisible labour” or “cognitive labour”. Sometimes “worry work”, which isn’t entirely inaccurate but smells demeaning. Ben does his fair share, there’s no question about that. He gets our daughter up, dressed and to school. He buys the dog food. I don’t know which day is bin day. Or where the stopcock is. Or the iron. But food is life, and I want my husband to be able to create something once a week that satisfies us both, something that he has thought about in advance and which doesn’t involve fish and chips. I crave a single evening off the mental load of providing for us. And did I mention it’s incredibly sexy when a reluctant husband makes dinner?

The problem

The cause, in my eyes, of sub-par results, is Ben’s unwillingness to follow a recipe. Cooking isn’t an innate skill. I wouldn’t try and fix the car with no guidance, so it feels bullish when people feel they can ace dinner with no experience or forethought. But the problem, in Ben’s eyes, is that years of high expectations (mine) have undermined his confidence to the extent that he is now too apprehensive of disappointing me in the kitchen to try.

So this is where we find ourselves, 12 years on, with me passing him The Secret of Cooking (£28, 4th Estate), the first cookbook from food journalist Bee Wilson, who has just won the Guild of Food Writers 2023 award for Food Writing. Wilson is not a chef and the book is not at all cheffy. Instead, she sets out to share everything she has learnt in several decades of writing about food, feeding herself and her family.

The book aims to be a gentle demystification of the kitchen, explaining how and when to cut corners, why not to panic about owning many kinds of oil, or whether all butter should be unsalted. There’s a chapter called ‘Teach yourself to cook with a carrot’ covering roasted, baked, mashed, grated, poached and seared, and very useful sections on ‘What no one tells you about cooking’ and ‘Why all recipes are incomplete’.

I feed Ben nuggets of the best bits, hoping to spark his interest. “The secret of cooking is the person who cooks,” Wilson writes. I realise I should re-route my attention from what Ben is cooking to Ben himself, if I am to hope for any long-term improvement.

The first try

I suggested he choose the dishes he most liked the look of. See? I am fully capable of relinquishing control. The black bean ragù has only a few ingredients – black beans, aubergine, tomato, miso paste – and comes from the chapter called “Cooking from a standing start”. A very wise choice for a novice on a weekday, even if the result is, as Wilson says herself, quite “studenty”.

Ben slops a rugby team-sized portion on top of egg noodles. I helpfully suggest we pretty it up with mashed avocado and soured cream. He is delighted with the result and praises the recipe for being easy to follow without patronising. I am delighted the recipe has yielded enough for two dinners, two lunches, and two portions for the freezer.

His only complaint is that it took him longer than the advertised 20 minutes, given the need for 10 or 15 minutes to chop two aubergines. OK. Nourish the cook, I remind myself. His pet hate is recipes that claim to be “easy”, “quick” and “foolproof” and turn out to be nothing of the sort, denting a fragile cook’s nascent courage in the process.

Progress?

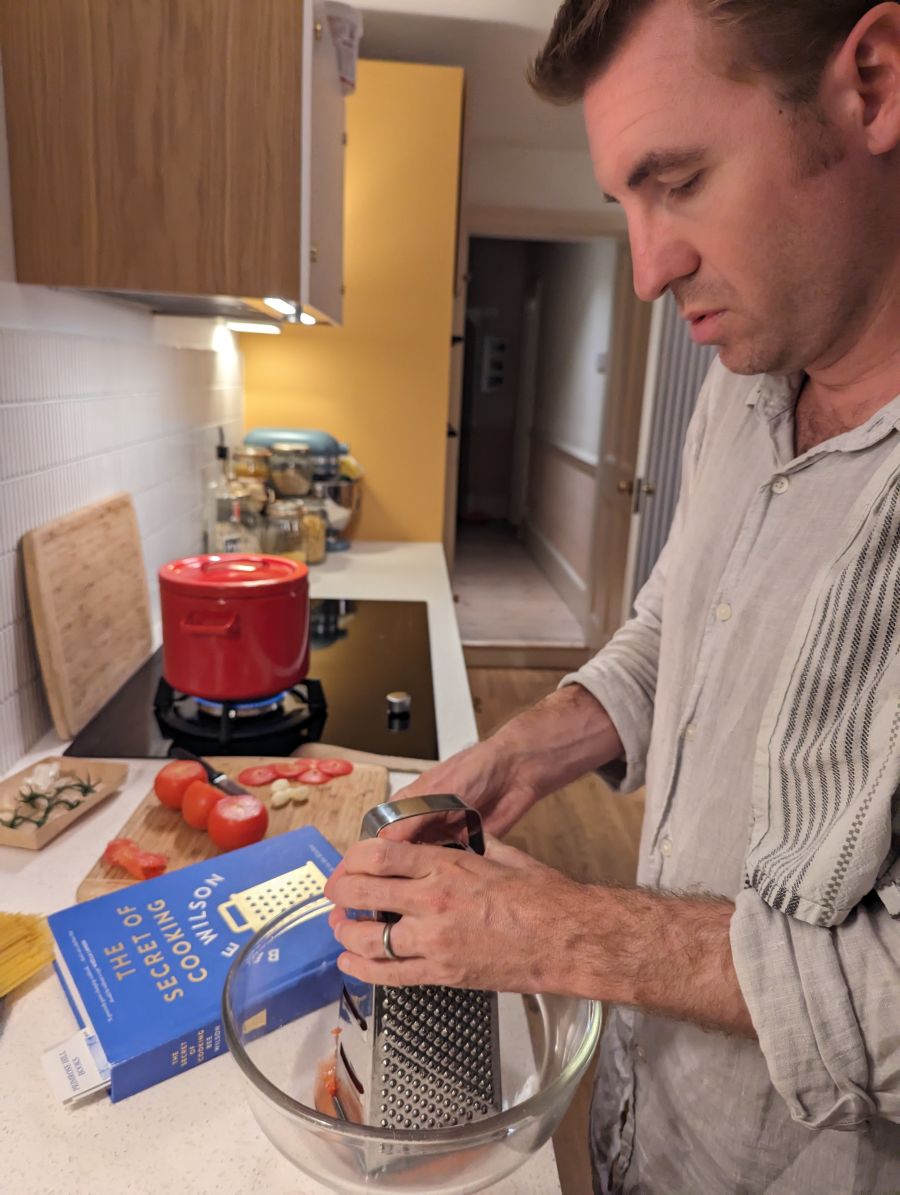

The second recipe he chooses, “Grated tomato and butter pasta”, makes an almost instant sauce of tomatoes by running them through a box grater. It is fresh and rich all at once. He doesn’t even overcook the spaghetti. I feel like our dinner-time relationship is evolving thanks to the secrets of this book. Also I’m on track for absolute vindication given I’ve always said our salvation lies in a cookbook, it’s just a case of finding the right one.

“The secret of cooking is that there is no secret formula, no special sauce, no hidden element,” I read, close to the end of The Secret of Cooking. But I know that for Ben so many of the things I do regularly in the kitchen are great mysteries, and why wouldn’t they be to a person who spends little time cooking?

But, continues Wilson: “The only universal secret is to find the recipes and methods that will make the person cooking feel more able to do it. Your comfort, ease and pleasure in the kitchen must come first…spending more time and effort on cooking can be completely worth it if you will enjoy either the process or the end results (or ideally, both).”

Have we made any progress? Ben has agreed to cook again next week and I have agreed not to get involved. I’ve already spotted a red flag in the chosen recipe, so only time will tell if I can keep quiet until he spots it for himself.

Bee Wilson’s The Secret of Cooking (£28, 4th Estate), is available now